A Meta-analytic Review of Prolonged Exposure for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

The efficacy and acceptability of exposure therapy for the treatment of mail service-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-assay

BMC Psychiatry book 22, Article number:259 (2022) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is common among children and adolescents who have experienced traumatic events. Exposure therapy (ET) has been shown to be effective in treating PTSD in adults. Nevertheless, its efficacy remains uncertain in children and adolescents.

Aims

To evaluate the efficacy and acceptability of ET in children and adolescents with PTSD.

Method

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest, LILACS, and international trial registries for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessed ET in children and adolescents (anile ≤18 years) with PTSD up to August 31, 2020. The primary outcomes were efficacy (the endpoint score from PTSD symptom severity rating scales) and acceptability (all-crusade discontinuation), secondary outcomes included efficacy at follow-upward (score from PTSD scales at the longest signal of follow-up), depressive symptoms (end-point score on depressive symptom severity rating scales) and quality of life/social functioning (end-bespeak score on quality of life/social functioning rating scales). This study was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020150859).

Consequence

A total of 6 RCTs (278 patients) were included. The results showed that ET was statistically more efficacious than control groups (standardized hateful differences [SMD]: − 0.47, 95% confidence interval [CI]: − 0.91 to − 0.03). In subgroup analysis, exposure therapy was more efficacious for patients with unmarried blazon of trauma (SMD: − ane.04, 95%CI: − one.43 to − 0.65). Patients with an average historic period of 14 years and older, ET was more constructive than the control groups (SMD: − ane.04, 95%CI: − 1.43 to − 0.65), and the intervention using prolonged exposure therapy (PE) (SMD: − 1.04, 95%CI: − 1.43 to − 0.65) was superior than control groups. Results for secondary outcomes of efficacy at follow-up (SMD: − 0.64, 95%CI: − 1.17 to − 0.10) and depressive symptoms (SMD: − 0.58, 95%CI: − 0.93 to − 0.22) were like to the previous findings for efficacy outcome. No statistically meaning effects for acceptability and quality of life/social operation were found.

Conclusion

ET showed superiority in efficacy at post-handling/follow-upwards and depressive symptoms comeback in children and adolescents with PTSD. Patients with single blazon of trauma may do good more from ET. And ET is more constructive in patients fourteen years or older. Moreover, PE could be a better choice.

Background

Mail service-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most common and typical continuous severe psychological disorder in individuals later on exposure to an unusual threatening or catastrophic event [ane,2,3,4]. Children who feel traumatic events may develop PTSD at higher rates than adults [v, 6]. It is reported that the overall rate of PTSD in trauma-exposed children and adolescents was 15.9% [vii]. If PTSD is not treated, information technology may lead to additional psychiatric disorders such as depression, feet disorders, with functional impairment during both childhood and adulthood [8]. In many cases, PTSD tin can turn into a chronic disease, leading to considerable affliction burdens and social and occupational disorders, huge economical and social costs and increased suicide take a chance [9, 10].

The psychotherapy is recommended past several clinical guidelines as the initial handling of PTSD in children and adolescents [11,12,xiii,fourteen]. In order to adequately process traumatic memories and ultimately eliminate fear, patients must reactivate their unwanted memories, and safe ingredients should be implanted [15]. Exposure therapy (ET), for traumatic memories, aims to bargain with information including trauma situation and related emotions, thoughts and behaviors. ET has demonstrated its efficacy in the treatment of phobias, anxiety and PTSD in adults [16]. At that place are many kinds of exposure therapy available now, including prolonged exposure (PE), narrative exposure therapy (Net), child narrative exposure therapy (KIDNET), etc. PE is a specific exposure-based type of cognitive behavior handling for PTSD, and it is widely accustomed in adults [17], past safety confrontation with thoughts, memories, places, activities and the people that have been avoided since a traumatic event occurred [18]. NET is a manualized, brusk-term, individual intervention program for the treatment of PTSD, based on CBT principles [nineteen]. NET has been adapted for the use with traumatized children and adolescents in a version chosen KIDNET [xx].

However, the gradual promotion of PTSD exposure therapy has acquired some controversies in the treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents, which was mainly related to ethical aspects and condom bug [21]. A loftier drop-out rate of exposure therapy was reported because of the too low or too high patient appointment in the recalled memories during the treatment [22, 23]. Evidence from studies in the clinical settings among children was limited [24]. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to systematically evaluate the efficacy and acceptability of exposure therapy in the handling of PTSD in children and adolescents.

Method

The protocol of this meta-analysis has been registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42020150859). The data that support the findings of this study is publicly available in Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/d6m4xhwtyw.3. Nosotros divers the main structured research question describing the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design (PICOS) in accord with the recommendations by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) groups [25].

Search strategy and option criteria

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, Spider web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest Dissertations, LILACS, international trials registers (such equally Earth Health Organization trials portal, ClinicalTrials. gov and Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry) including published and unpublished trials, from the date of database inception to August 31, 2020. Nosotros put no restrictions on language. We searched with dissimilar combinations of the following keywords: Condition = (posttrauma* OR mail service-trauma* OR post trauma* OR trauma* OR PTSD OR Post-traumatic stress symptoms OR PTSS OR acute stress disorder* OR peritrauma* OR peri-trauma* OR avoidant disorder* OR combat disorder* OR war neurosis OR Schreckneurose OR fear neuroses OR shell shock OR sexual activity*-abus* OR sex activity* abus* OR terror* OR war OR conflict* OR violen* OR acciden* OR shoot* OR disaster* OR earthquake OR tornado OR flood OR tsunami* OR hurricane* OR fire OR maltreat* OR crash* OR expiry OR grief) AND Intervention = (psychother* OR psychological OR cognitive-behavio* OR cognitive-behavio* OR behavio* OR cogniti* OR CBT OR exposure therapy OR exposure handling OR exposure-based behavior therapy OR exposure-based OR exposure*).

Our inclusion criteria were every bit follows: (i) randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (ii) participants were children and adolescents (aged ≤18 years) who met the criteria for PTSD diagnosis: a. for patients with complete PTSD, according to the standardized diagnosis based on the international classification (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] [26,27,28,29,30], the International Classification of Diseases [ICD] [31, 32] or validated scales for PTSD based on DSM/ICD criteria [33,34,35,36]); b. patients with subclinical PTSD, defined as those who have experienced psychological trauma, present with at least one of the iv symptom groups described in DSM-5 and reported some subsequent symptoms of PTSD, including re-experiencing, avoidance, overreaction, and negative cognitive and emotional changes; c. patients with clinically pregnant symptoms of PTSD, that was, the score of the patient scale was higher than the effective threshold of the PTSD rating calibration; (three) the intervention was exposure therapy, including PE, NET, KIDNET, etc.; (iv) there were more than x participants per study; (v) the interventions of the control group were active control groups (ACG), treatment as usual (TAU), and waiting listing (WL). The ACG could include supportive unstructured psychotherapy, nondirective supportive treatment and child-centered therapy.

The initial screening was based on the title and abstruse past ii researchers (T.H and Fifty.H) independently. Publications were excluded from the search results if they did non come across the aforementioned inclusion criteria. Any disagreement during the procedure was resolved past discussing with senior reviewing authors (Y.X and X.Z). We contacted the corresponding authors in request for the information missing from the publication that was necessary for conducting the analysis. If the authors did not respond with the sufficient data to perform the meta-assay or did not respond, the studies were excluded.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (T.H and Fifty.H) extracted the relevant parameters from the original paper, including the titles of the studies, patient characteristics (including type of trauma, diagnostic criteria for PTSD, severity of PTSD symptoms, the sample size, hateful historic period and gender of participants), intervention details (including blazon of interventions, number of sessions, treatment duration, follow-upwards elapsing). If at that place was a disagreement betwixt ii reviewers, we resolved the disagreement by discussing with the senior review authors (Y.X and Ten.Z).

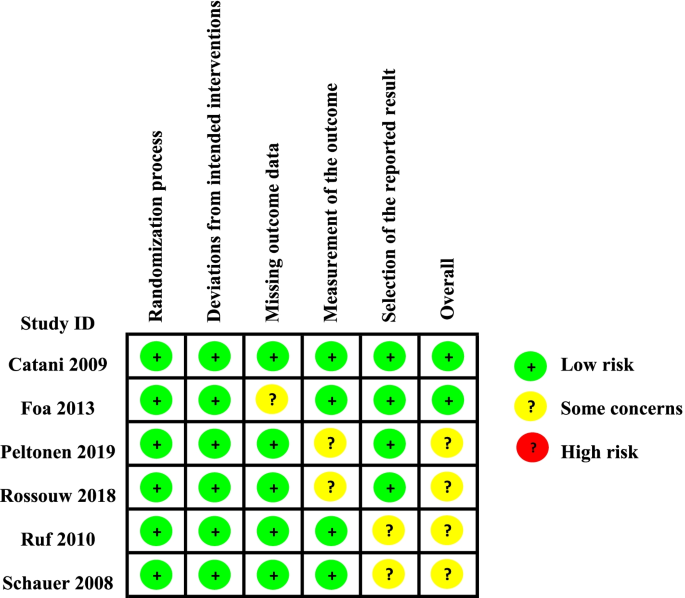

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (Due south.T and South.Ten) assessed the methodological quality of the included studies independently. According to the Cochrane Collaboration'due south tool V.2.0, the risk of bias was rated as 'low risk', 'high gamble' or 'some concerns' in the post-obit domains: (ane) bias arising from the randomization process (Systematic differences in baseline characteristics of the comparison groups); (ii) bias due to deviations from intended interventions (Systematic differences in care, exposure factors, etc. between groups, other than the intervention of interest); (3) bias due to missing result data (Systematic differences due to dropout of cases between groups); (iv) bias in measurement of the upshot (Systematic differences in the measurement of outcomes between groups); (v) bias in selection of the reported result (Systematic differences between reported and unreported results). The disagreement betwixt two reviewers was resolved by discussing with the senior review authors (Y.10 and 10.Z).

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were the efficacy (as measured by the endpoint score from PTSD symptom severity rating scales completed by children, parents or clinicians) and acceptability (every bit the percentage of people who had dropped out from the study for any reason) of mail-treatment. Assessment methods such equally the Child PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview (CPSS-I), the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPs) were used to measure out the curative result of complete exposure therapy for the treatment of children and adolescents with PTSD. If more than than one calibration was reported in a trial, we chose the scale with the highest ranking according to a hierarchy based on psychometric properties and appropriateness, which was divers in our previous registered protocol. If the trial had different raters of the assessment of PTSD symptom severity rating calibration, self-written report was prefered [37]. Secondary outcomes included efficacy at follow-upwards (measured past the score from PTSD scales at the longest point of follow-up up to 12 months), depressive symptoms (measured by the stop-point score on depressive symptom severity rating scales), quality of life and functional improvement (QoL/functioning) (measured by the end-point score on QoL/functioning rating scales).

Statistical assay

Analyses were conducted by using the Review Managing director, Version 5.three and Stata 16.0. Continuous variables were estimated past pooled standardized mean differences (SMD, hedge's g) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Nosotros weighted the within-report and between-study variance according to the size of the sample size of each independent study, taking into account the sampling error of the study and the mistake of the true upshot size [38]. The binary variables were estimated by pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. The significance of the pooled SMDs or ORs was estimated by Z exam (P < 0.05 was considered statistically meaning). The Iii-based Q statistic exam was performed to evaluate variations due to heterogeneity rather than chance. A random-effects or fixed effects methods model was used to calculate the pooled effect estimates in the presence (P < 0.05) or absence (P ≥ 0.05) of heterogeneity. Nosotros assigned adjectives of low, moderate, and high to Itwo values of 25, 50, and 75% [39].

Considering the possibility that effectiveness may differ according to different parameters, we conducted various subgroup analyses of the parameters equally following: (1) single type of trauma vs. multiple types of trauma; (ii) PE vs. NET vs. KIDNET; (3) treatment elapsing ≥12 weeks vs. treatment duration < 12 weeks [forty]; (4) mean age < xiv years vs. mean historic period ≥ 14 years. We also performed sensitivity analyses by omitting RCTs published in a significantly dissimilar year than the others, or RCTs with non-blinding assessment, or RCTs with a modest sample size. All tests were 2-sided, and statistical significance was defined as a probability P value of < 0.05.

Results

Study characteristics

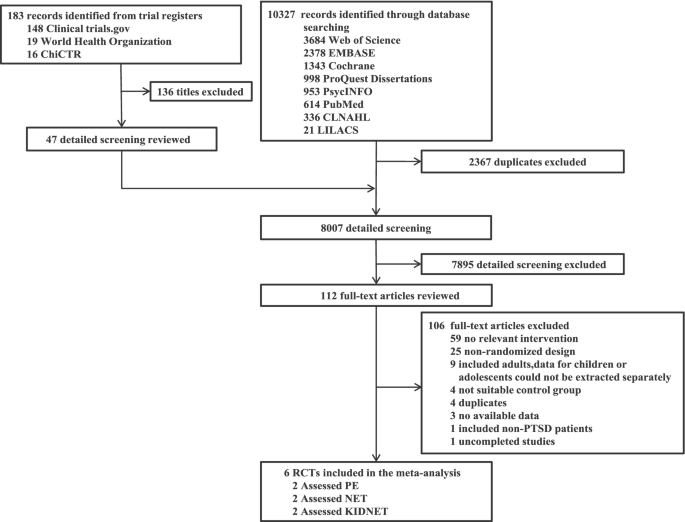

Through searching the databases and international trials registers mentioned above, 10,510 citations were identified and 112 potentially eligible articles were reviewed in total text. In total, six clinical trials were included in the present written report. The flow diagram was shown in Fig. 1. Six randomized controlled trials (n = 278) comparing ET (n = 145) with control conditions (northward = 133) were included, the clinical and methodological characteristics of included trials were summarized in Table one. The mean age was thirteen.84 years onetime (SD = ii.33) and 69.1% were females. ii RCTs [41, 45] (33.33%) were conducted in Sri Lanka (n = 78), and four (66.67%) from other countries (Germany, Finland, S Africa, etc.). The mean study sample size was 46, ranging from 26 to 63 patients. Trauma types included trauma from the war [45] (north = 78), sexually abused [42] (north = 61), mixed [46] (n = 123) and others.

Flow nautical chart of study selection. Abbreviations: PE = Prolonged Exposure Therapy, NET = Narrative Exposure Therapy, KIDNET = Narrative Exposure Therapy for children

Primary outcomes

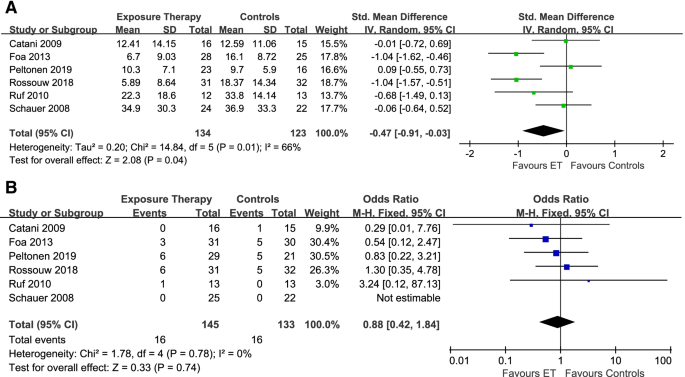

For evaluating the efficacy of ET in reducing the post-treatment PTSD symptom severity, 6 articles (north = 257) with a moderate significant heterogeneity (I2 = 66%, P = 0.01, Fig. 2A) were included [24, 41, 44, 46, 47]. The results showed that ET was more effective than control groups (SMD: − 0.47, 95%CI: − 0.91 to − 0.03). For acceptability, 6 studies [24, 41, 42, 44, 46, 47] (north = 278) with no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.78, Fig. 2B) were included and there were no significant differences between the treatment group and the control group (OR: 0.88, 95%CI: 0.42 to 1.84).

The efficacy (A) and acceptability (B) of exposure therapy at mail-treatment

Secondary outcomes

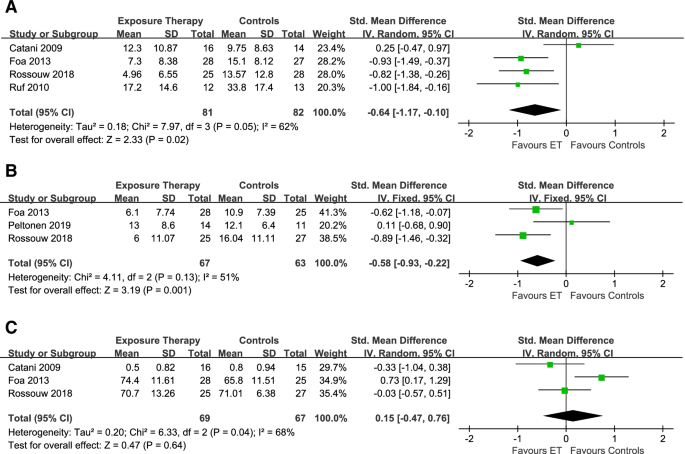

For the effects of follow-up, four studies [41, 42, 44, 47] with moderate heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 62%, P = 0.05, Fig. 3A) were eligible (n = 163). Exposure therapy was statistically significantly more efficacious than command conditions (SMD: − 0.64, 95%CI: − 1.17 to − 0.10). For assessing the effects of handling on depressive symptoms, we included iii studies [24, 42, 47] (northward = 130) with not-significant low heterogeneity (I2 = 51%, P = 0.13, Fig. 3B), and the exposure therapy were more efficacious than control groups (SMD: − 0.58, 95%CI: − 0.93 to − 0.22). In terms of the furnishings of quality of life/social functioning, 3 trials [41, 42, 47] (n = 136) were included with statistically pregnant moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 68%, P = 0.04, Fig. 3C). There were no meaning differences at the end of treatment (SMD: 0.15, 95%CI: − 0.47 to 0.76).

The efficacy of exposure therapy at i–12 months follow-upwards (A), the effect of exposure therapy on depressive symptoms (B), and the effects of exposure therapy on quality of life/social operation (C)

Subgroup analysis

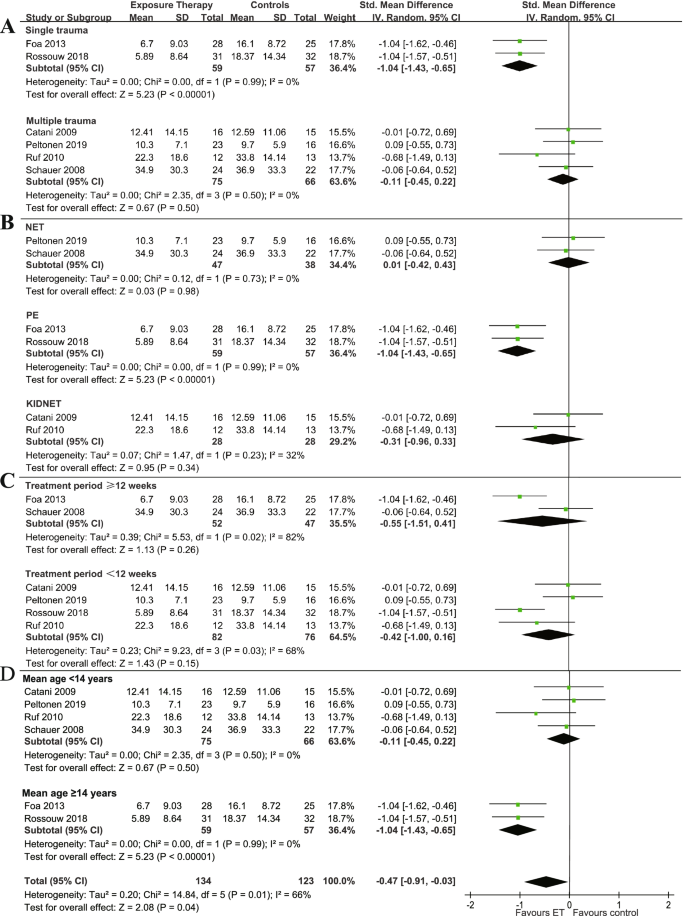

In the subgroup analysis of the post-treatment efficacy amid patients who suffered multiple types of trauma, no meaning difference was constitute between exposure therapy and control groups (SMD: − 0.eleven, 95%CI: − 0.45 to 0.22; Iii = 0%, P = 0.l, Fig. 4A). For patients who suffered single type of trauma, exposure therapy was statistically more than efficacious than control groups (SMD: − i.04, 95%CI: − ane.43 to − 0.65; I2 = 0%, P = 0.99). The intervention method using PE equally the experimental grouping (SMD: − ane.04, 95%CI: − i.43 to − 0.65; I2 = 0%, P = 0.99, Fig. 4B) was more effective than command groups, but groups using Net (SMD: 0.01, 95%CI: − 0.42 to 0.43; I2 = 0%, P = 0.73) or KIDNET (SMD: − 0.31, 95%CI: − 0.96 to 0.33; I2 = 32%, P = 0.23) were not. For patients whose handling sessions were more than than 12 weeks (SMD: − 0.55, 95%CI: − 1.51 to 0.41; I2 = 82%; P = 0.02, Fig. 4C) or less than 12 weeks (SMD: − 0.42, 95%CI: − 1.00 to 0.16; Itwo = 68%, P = 0.03), exposure therapy was not more effective than control groups. For patients with an average age of less than xiv years, ET did not bear witness a pregnant difference between ET and the command groups (SMD: − 0.11, 95%CI: − 0.45 to 0.22; I2 = 0%, P = 0.50, Fig. 4D). For patients with an average age of 14 years and older, ET was more effective than the command groups (SMD: − i.04, 95%CI: − one.43 to − 0.65; I2 = 0%, P = 0.99).

The subgroup analysis of the efficacy at postal service-handling

Quality cess

As assessed with Risk of bias tool 2.0 (ROB ii.0), ii RCT [37, 41] was rated as low risk, and four RCTs [24, 42, 44, 46, 47]were rated as some concerns (Fig. five).

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements virtually each risk of bias item presented every bit percentages across all included studies

Discussion

This meta-assay is aimed to assess the efficacy and acceptability of exposure therapy in the treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of exposure therapy in children and adolescents with PTSD. We found that exposure therapy showed college efficacy than command groups at post-treatment/follow-up and depressive symptom, only the acceptability did not perform ameliorate. Subgroup assay showed that patients with single type of trauma may benefit more from exposure therapy. And PE showed a significant advantage over Net and KIDNET. This meta-assay may provide insights for the clinical treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents.

It has been proved that ET showed a significant advantage in treating adults [xl, 48] and has been recommended every bit the starting time-line therapy for adults' PTSD [xvi, xl]. This study showed a similar event in terms of PTSD in children and adolescents. Owing to the mechanisms of ET, information technology can activate the traumatic retention and inserted the safe components [49], so that ET has good efficacy of PTSD. Besides, subgroup analysis showed PE had significant advantages in the treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents. The possible reasons could be the following: Firstly, PE is an exposure-based CBT of PTSD and has been in development since 1982 [16]. Therefore, PE has been widely studied with more comprehensive evidence for PTSD. Secondly, PE is an extensively studied course of individual CBT, the adaptation emphasizes developmental sensitivity, modularity, and flexibility [16]. In addition to the core ET components of psychoeducation and exposure, PE includes more extensive case management and relapse prevention component, which could contribute to the benefits of PE [16]. For NET, on the other hand, the fear structure needs to exist activated in a prophylactic environment to decrease maladaptive associations [19]. During re-experiencing of the traumatic events (such as through nightmares, intrusive thoughts, or flashbacks), the fearfulness network becomes reinforced because of the additional layer of emotional distress, and the memory is thus more than susceptible to beingness triggered later [nineteen]. Subgroup analysis showed that exposure therapy was more than effective for children and adolescents with single type of trauma. However, this conclusion should exist treated with circumspection due to the limited number of studies included. The trauma types of patients in the present report were more than comprehensive compared with the previous written report [50]. Four out of half dozen studies in our meta-analysis included patients with multiple trauma types. For example, i of our studies [46] included the teenagers who suffered natural disasters, traffic accidents, or sexual assault. These results were consistent with previous studies [51, 52]. Since patients who experienced multiple types of trauma are more susceptible to circuitous PTSD including (in add-on to the cadre PTSD symptoms of re-experiencing, abstention, and hyperarousal) disturbances in affect regulation, dissociation, self-concept, interpersonal relationships, somatization, and systems of significant [53], complex mental illnesses may have a negative bear on on the treatment results of PTSD patients [54], leading to unhealed trauma. And uncured trauma is a common cause of refractory depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder [55].

Our analysis suggested that ET may generally result in better outcomes than command conditions in the long-term follow-upwards. When treating children and adolescents with trauma, information technology may be important to not only tackle the one event in their traumatic history, merely likewise all the events that may however cause PTSD symptoms. The clinical model of repeated traumatization underlying ET draws on dual representation theories of PTSD and emotional processing theory and the idea of fearfulness networks [56]. ET constructs a narrative that covers the patient's entire life, while giving a detailed account of past traumatic experiences, which can contribute to the long-term efficacy [16]. For acceptability, no significant difference was observed between ET and control groups. Yet, from the patient's perspective, specially for children and adolescents, exposure therapy is challenging and its treatment procedure can be relatively painful [15]. Traumatic feel is required to reproduce on the patient, which may crusade agin effects. The treatment cycle is besides relatively long [16]. In the treatment duration ≥12 weeks and < 12 weeks, the issue was not pregnant difference. At nowadays we didn't find more relevant literature to make comparing on this outcome, nosotros may need more than studies on the correlation between dissimilar treatment duration and handling results in the future. What'southward more than, nosotros plant a deviation in the effectiveness of interventions for PTSD symptoms in children (< 14 years) and adolescents (≥ fourteen years) at postal service-treatment. The results showed that exposure therapy was not superior than control groups on children, while it was more effective than control groups for adolescents. These results are consequent with the findings of earlier studies [42, 43, 50], where exposure therapy was constitute to exist superior to control groups in terms of PTSD symptom reduction. However, for children, exposure therapy didn't show better performance than treatment strategies in other control groups. This can exist attributed to the often chronic and recurrent nature of PTSD symptoms [57]. Some studies [58, 59] suggests that prior to age xiv teens get more emancipated from adult government while identifying more with the emergent norms of their peers, and later historic period 14 their created identity is internalized. And we remember this character changes may correlate with our results.

Because PTSD patients ordinarily take comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety [60, 61], we too considered the efficacy of exposure therapy for PTSD comorbidities. This study showed that exposure therapy tin significantly better patients' depressive symptoms. Regarding the machinery of its effect on depression symptoms, ET may modify depression through cognitive shifts or exposure-induced emotional arousal [62] despite the lack of Socratic questioning, specific instruction nearly cerebral errors, and assigned practice. The specific mechanism is however unclear. However, these bespeak that ET could be an effective choice for PTSD patient comorbidity with depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. The patient's quality of life at the finish of treatment was non significantly improved. Nosotros speculated that this may be related to the relatively painful process of exposure therapy and further studies are needed.

Overall, our results provided some new perspectives on exposure therapy for PTSD in children and adolescents. We have tried to reduce the heterogeneity among studies by omitting RCTs that may cause significant bias in the results due to commodity characteristics (such every bit inappropriate report design, not-RCT, sample size less than 10, etc.). However, due to the following limitations, the results of this meta-analysis should exist interpreted carefully. First of all, this study included a small sample size. The scope of our literature search was as broad as possible, but subsequently screening papers in strict accordance with our standards, simply half dozen studies were included. Ane of the reasons for the express number of studies is the high drop-out rate and the limited number of RCTs for children and adolescents with PTSD. Every bit the mental wellness of children and adolescents is essential to the sustainable development of society, nosotros decided to attach to this theme. The reasons for the high drop-out rate include: a. the determination of discontinuing the treatment by the patients themselves or their parents because of the feeling that the treatment was no longer needed [24]; b. the difficulty of re-experiencing traumatic events every bit reported past Cyberspace clients [24]; c. the child populations in wars are normally on the move. 'Domicile' is often a Displaced People's Campsite, a Cross border Transit or Refugee Campsite. It is challenging to extend private services, which last several weeks if not months [46]. Some other reason for the limited number studies is that psychotherapy for children and adolescents requires systematic and standardized preparation, which is more difficult than meliorate quantitative evaluation of drug therapy. In add-on, exposure therapy can evoke traumatic memories in children and adolescents, which may business relationship for the small number of variables included in this studies. Secondly, most of the analyzed studies presented with moderate to high heterogeneity. These could come up from the clinical and methodological characteristics. Some subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity, however, other important parameter such as symptom severity, gender, country of patients couldn't not be addressed due to the limitation of original information. Thirdly, the ROB two.0 showed most of the risk of bias of the included studies was rated as low risk and some concerns. These mainly came from the deviations from intended interventions, for the blinding. However, it was difficult to carry with double-blinding in psychotherapies. Fourth, due to the express number of included studies, no publication bias funnel plot was performed, and potential publication bias cannot be ruled out.

Determination

This meta-analysis constitute that ET showed superiority in terms of efficacy at postal service-treatment/follow-up and depressive symptoms comeback in treating PTSD in children and adolescents. Patients with unmarried type of trauma may do good more from the intervention of ET. ET is more than constructive in patients anile xiv years or older. Moreover, PE could be a better choice for children and adolescents with PTSD. Further well-divers clinical studies should exist conducted to confirm those outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are bachelor in the Mendeley repository, at https://doi.org/ten.17632/d6m4xhwtyw.iii.

References

-

Kessler RC, Galea South, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Ursano RJ, Wessely S. Trends in mental illness and suicidality afterwards hurricane Katrina. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(4):374–84.

-

Arnberg FK, Gudmundsdóttir R, Butwicka A, et al. Psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts in Swedish survivors of the 2004 Southeast Asia tsunami: a five year matched accomplice study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):817–24.

-

North CS, Smith EM, Spitznagel EL. One-year follow-up of survivors of a mass shooting. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(12):1696–702.

-

Lancaster SL, Melka SE, Rodriguez BF. Bryant ARJJoAM, trauma. PTSD symptom patterns following traumatic and nontraumatic events. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2014;23(4):414–29.

-

Luthra R, Abramovitz R, Greenberg R, et al. Human relationship between blazon of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among urban children and adolescents. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(11):1919–27.

-

McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:8.

-

Alisic East, Zalta AK, van Wesel F, et al. Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:335–40.

-

Lamberg Fifty. Psychiatrists explore legacy of traumatic stress in early life. JAMA. 2001;286(5):523–6.

-

Merz J, Schwarzer Thousand, Gerger H. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, and combination treatments in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):904–xiii.

-

Panagioti M, Gooding P, Tarrier N. Mail service-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal beliefs: a narrative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(6):471–82.

-

Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ. Guidelines for handling of PTSD. 2000;xiii(4):539–88.

-

Ponteva K, Henriksson M, Isoaho R, Laukkala T, Punamäki Fifty, Wahlbeck K. Update on current intendance guidelines: post-traumatic stress disorder. Duodecim; laaketieteellinen aikakauskirja. 2015;131(vi):558–9.

-

Steiner, Hans, John, et al. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. American University of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J Am Acad Kid Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(9):997–1001.

-

Morina N, Koerssen R, Pollet Telly. Interventions for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;47:41–54.

-

Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fright: exposure to corrective information. Psychol Balderdash. 1986;99(one):xx–35.

-

Mørkved N, Hartmann K, Aarsheim LM, et al. A comparison of narrative exposure therapy and prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(6):453–67.

-

Cukor J, Olden M, Lee F, Difede J. Evidence-based treatments for PTSD, new directions, and special challenges. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1208:82–9.

-

Foa EB, Hembree East, & Rothbaum BO. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences therapist guide. USA: Oxford University Printing. 2007;1.

-

Schauer Thousand, Neuner F, Elbert T. Narrative exposure therapy: A short-term treatment for traumatic stress disorders (2nd rev. and expanded ed.). Cambridge: Hogrefe Publishing; 2011.

-

Onyut LP, Neuner F, Schauer E, et al. Narrative Exposure Therapy as a treatment for child war survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: Two instance reports and a pilot study in an African refugee settlement. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;five:seven.

-

Kangaslampi S, Garoff F, Peltonen Yard. Narrative exposure therapy for immigrant children traumatized by war: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of effectiveness and mechanisms of change. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:127.

-

Markowitz JC, Petkova E, Neria Y, et al. Is exposure necessary? A randomized clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(5):430–40.

-

Landowska A, Roberts D, Eachus P, Barrett A. Inside- and between-session prefrontal cortex response to virtual reality exposure therapy for acrophobia. Front end Hum Neurosci. 2018;12:362.

-

Peltonen Grand, Kangaslampi Due south. Treating children and adolescents with multiple traumas: a randomized clinical trial of narrative exposure therapy. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1558708.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12.

-

Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

-

(APA) APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-Iii). 3rd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Clan; 1980.

-

(APA) APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-3-R). tertiary ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Clan; 1987.

-

(APA) APA. Diagnostic and statistical transmission of mental disorders (DSM-IV). 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

-

(APA) APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

-

(WHO) WHO. The Ninth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases and related health problems (ICD-9). Geneva: World Wellness Organization; 1978.

-

(WHO) WHO. The 10th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases and related health problems (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

-

Nader KONE, Weathers FW, et al. Clinician-administered PTSD scale for children and adolescents for DSM-Iv (CAPS-CA). National Center for PTSD & UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Plan collaboration: Los Angeles; 1998.

-

Pynoos RSRN, Steinberg A, et al. The UCLA PTSD reaction index for DSM-IV (revision ane). UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program: Los Angeles; 1998.

-

Kaufman JBB, Brent D, et al. Schedule for melancholia disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-nowadays and lifetime version (Thousand-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity information. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–eight.

-

Silverman WKAA. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

-

Moshier SJ, Bovin MJ, Gay NG, et al. Test of posttraumatic stress disorder symptom networks using clinician-rated and patient-rated information. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127(6):541–7.

-

Tang JL. Weighting bias in meta-analysis of binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1130–6.

-

Higgins J, Thompson SG, Decks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

-

Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:128–41.

-

Catani C, Kohiladevy M, Ruf M, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Treating children traumatized by state of war and tsunami: a comparison betwixt exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in Northward-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;nine:22.

-

Foa EB, Mclean CP, Capaldi S, Rosenfield D. Prolonged exposure vs supportive counseling for sexual corruption-related PTSD in adolescent girls: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(24):2650–vii.

-

Rossouw J, Yadin E, Alexander D, Seedat South. Prolonged exposure therapy and supportive counselling for post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents: task-shifting randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213(4):587–94.

-

Ruf K, Schauer G, Neuner F, Catani C, Schauer E, Elbert T. Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to sixteen-twelvemonth-olds: a randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(4):437–45.

-

Neuner F, Catani C, Ruf M, Schauer E, Schauer M, Elbert T. Narrative exposure therapy for the handling of traumatized children and adolescents (KidNET): from neurocognitive theory to field intervention. Kid Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17:3.

-

Schauer East. Trauma Treatment for Children in War: build-upwardly of an testify-based big-scale Mental Health Intervention in North-Eastern Sri Lanka. Kriegskinder; 2008.

-

Rossouw J, Yadin East, Alexander D, Seedat South. Long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial of prolonged exposure therapy and supportive counselling for post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents: a task-shifted intervention. Psychol Med. 2020:1–9.

-

Rauch SA, Eftekhari A, Ruzek JI. Review of exposure therapy: a aureate standard for PTSD treatment. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(v):679–87.

-

McNally RJ. Mechanisms of exposure therapy: how neuroscience can improve psychological treatments for anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(6):750–ix.

-

Gilboa-Schechtman E, Foa EB, Shafran N, et al. Prolonged exposure versus dynamic therapy for adolescent PTSD: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1034–42.

-

Priebe K, Kleindienst N, Schropp A, et al. Defining the alphabetize trauma in mail-traumatic stress disorder patients with multiple trauma exposure: impact on severity scores and handling furnishings of using worst unmarried incident versus multiple traumatic events. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;9(1):1486124.

-

Loos S, Wolf Due south, Tutus D, Goldbeck L. Frequency and type of traumatic events in children and adolescents with a posttraumatic stress disorder. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2015;64(8):617–33.

-

Ottisova L, Smith P, Oram S. Psychological consequences of man trafficking: complex posttraumatic stress disorder in trafficked children. Behav Med. 2018;44(iii):234–41.

-

Goddard E, Wingrove J, Moran P. The touch of comorbid personality difficulties on response to IAPT treatment for depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2015;73:1–7.

-

Ho GWK, Hyland P, Shevlin M, et al. The validity of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in eastward Asian cultures: findings with immature adults from Communist china, Hong Kong, Japan, and Taiwan. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1717826.

-

McLean CP, Foa EB. Prolonged exposure therapy for mail-traumatic stress disorder: a review of evidence and dissemination. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;eleven(viii):1151–63.

-

Deblinger E, Steer RA, Lippmann J. Two-year follow-up written report of cerebral behavioral therapy for sexually abused children suffering post-traumatic stress symptoms. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23(12):1371–8.

-

Zohar AH, Zwir I, Wang J, Cloninger CR, Anokhin AP. The development of temperament and graphic symbol during adolescence: the processes and phases of change. Dev Psychopathol. 2019;31(two):601–17.

-

Gaete V. Adolescent psychosocial development. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2015;86(6):436–43.

-

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-4 disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Curvation Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(six):617–27.

-

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes Yard, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–60.

-

Thompson-Hollands J, Marx BP, Lee DJ, Resick PA, Sloan DM. Long-term treatment gains of a brief exposure-based handling for PTSD. Depress Feet. 2018;35(10):985–91.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sihao Gao for his comments on the draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported past the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81873800); the High-level Talents Special Back up Plan of Chongqing (grant T04040016) and the institutional funds from the Chongqing Science and Engineering science Committee (grant cstc2020jcyj-jqX0024).

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

T.H and L.H contributed equally to this work. X. Z and Y. X share the senior writer position. T.H and Fifty.H wrote the main manuscript text. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript text. S.T and S.Ten assessed the methodological quality of the included studies independently. Southward.T and T.H prepared Figs. S.X prepared Table 1. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Respective authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics blessing and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

X.Z reported receiving lecture fees from Janssen Pharmaceutica and Lundbeck, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing involvement.

Additional data

Publisher'south Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilize, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, every bit long as you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and signal if changes were fabricated. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the commodity'due south Artistic Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you volition need to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/iv.0/. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the information fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this commodity

Cite this article

Huang, T., Li, H., Tan, S. et al. The efficacy and acceptability of exposure therapy for the treatment of mail service-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-assay. BMC Psychiatry 22, 259 (2022). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12888-022-03867-6

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12888-022-03867-half dozen

Keywords

- Exposure therapy

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Children

- Adolescents

- Meta-analysis

Source: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-022-03867-6

0 Response to "A Meta-analytic Review of Prolonged Exposure for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder"

Post a Comment